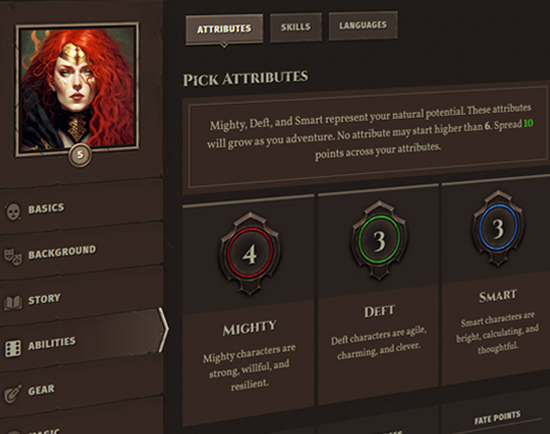

While the core mechanic in OSR+ is as simple as d6 + attribute + skill, the GM has a number of choices when it comes to structuring that roll for the resolution of PC action. Understanding when to use each type of check is key to mastering the system as a GM.

The core mechanics of OSR+ are outlined in greater detail in the core rules, but in the absence of a (forthcoming!) game master's guide, I thought I'd outline the reasoning behind when you might choose an opposed check vs. an unopposed check vs. a success check. And there's also scene checks! Don't worry, it's actually not that complicated. Let's dive right in.

Tools, Not Rules

Part of the spirit of the OSR movement is the philosophy of "tools, not rules." The rules of OSR+ exist to help you resolve uncertainty in the fiction, they're not manacles to bind you to solving problems in a specific way every time. While resolving action in the fiction in a consistent way is something to be cultivated as a GM, it's more important to understand why you're resolving something in a certain way and to be committed to that reasoning while doing it.

Ninety percent of the resolutions you're going to have to make can use one of these three mechanics:

(There's also a scene check, but we'll get to that later.)

Opposed Checks

Opposed checks are my favorite because they take my judgment out of the equation. They are binary checks with a winner and a loser: an equal result means both succeed (nobody wins). Put quite simply, you use an opposed check when you have the option to compare results from two or more actors in the fiction: an NPC and a PC; a PC and a PC, as examples.

Examples of opposed checks:

- People stabbing each other (attack vs. defense check). Combat in particular has its own subset of rules, but it really boils down to a skill check (with a weapon) vs. a defense check by the defender.

- An arm-wrestling match with a giant squid (a Mighty check). Does the squid have Athletics? Let's hope you do. Compare the results.

- A satanic spelling bee (opposed skill check). It's a battle of wits between you and spelling bee champion Satan, who has Domain Knowledge: Linguistics and the story tag "Spelling Bee Champion."

Unopposed Checks

Unopposed checks require you to decide the target number (TN) of the roll on the fly, but they are the simplest and fastest to resolve. Such checks are meet or beat with a pass/fail result. You use an unopposed check to resolve action PCs take when the thing they're trying to overcome in the fiction has no stats of its own, but still poses a chance of failure.

Examples of unopposed checks:

- Jumping across a rooftop with a horde of angry cannibals below (likely a Mighty check). You either make it or you fall. How far apart are the rooftops? Are there external pressures that will jeopardize the jump? You don't consider the PC's competence when choosing the target number—only the situational factors matter.

- Catching the sacred vase before it falls into lava while you're freefalling out of a plane (probably a Deft check). The lava, the descent, the fragility of the vase, and the Nazis firing machine guns from the plane might all factor into choosing a target number.

- Diffusing a clockwerk bomb that is about to explode (likely a Reflexes or Smart check). Cutting the right wire is a zero-sum game. Are you rattled from shooting your way into the vault? Are the disarming instructions written in Phoniq and you have no idea what they say?

Success Checks

Success checks are the most fun of all the checks, but take more time to resolve out-of-character, and require creative input on your part. This check isn't determining whether you fail or succeed, in fact it's assuming you succeed and measuring how impactful your action is on the fiction. You use a success check when the PC's action can't fail or if you need to gauge their success depending on how well they perform. For such a check, the player rolls as high as they can, and you consult the Success Check table to determine how to interpret the result.

Examples of success checks:

- Canvassing your network for dirt on the king (Survival check). Rolling with player advantage might let you surface your own incriminating evidence; rolling poorly might get you the details while also exposing your subterfuge to the king's spies.

- Delivering a speech to inspire the troops (Influence check). Rolling with GM advantage might prompt the GM to bestow some mechanical advantage on the troops in the upcoming battle; rolling poorly might only improve the morale of your most loyal soldiers, and leave the rest unmoved.

- Consulting the lore of the dead god to learn its secrets (Lore check). A clean success might get you exactly the information you need and nothing more; success at a cost might prompt the GM to offer you a choice between two secrets, one of which is false.

You Have Options

Remember that it's possible to resolve any given situation in multiple ways, so you should always first encourage players to suggest a plan of attack.

For example, convincing the reluctant noble to help the party can be approached in a number of ways:

- You can try reasoning with him that joining in your cause is the best course of action for the health of his realm (likely an opposed Smart check). That, or seducing him (a Performance check).

- You can stage an elaborate banquet to make him more amenable to lengthy discussion to take advantage of the Rogue's skill Craft: Fine Cuisine (in which case a success check might make sense).

- You could expand the scenario into social combat and set up windows of success during which the you can attempt to win over the noble with various checks vs. his social defense.

When players suggest one of these examples, they're not only helping you decide how to resolve their action in the fiction, but they're also telling you the sort of scene they want to play through. The master debater or seductress in #1 wants to get things over with quickly. The daring cooks in #2 are open to hijinks and an extended scene, in the event their caper goes awry. The loquacious elocutors in #3 might be interested in some downtime with the noble, in order to resolve the action over a longer period of in-character time.

Picking a Lock

Picking a lock, similarly, is a problem that can be approached in a number of ways.

Generally, the lock can't roll against you, unless its creator has stats that we can roll on its behalf, so an opposed check is out. If there isn't enough time to pick the lock before the guards get you, the GM might assign the lock a target number to beat based on the quality of its design. And if you have all the time in the world to pick the lock, then a success check might be plausible to introduce unforeseen complications (an additional hidden security system that might get tripped on success at a cost, or perhaps the treasure has already been stolen on a poor result).

The point of having all these checks as options is to enable you, as the GM, to decide when uncertainty can lead to interesting outcomes, and when uncertainty needs to be dealt with quickly and efficiently.

Scene Checks

Finally, scene checks. These are about resolving an entire scene over the course of three rolls called acts. Scene checks take the most out-of-character time of all checks, but they also save the most in-character time because they tend to compress a bunch of actions PCs are taking into a single roll.

You can use scene checks when all the specific things PCs have to do to solve the problem in the fiction aren't as interesting as the problem itself. For example, "sneaking into the evil fortress" is made up of a bunch of discreet actions the PCs can take, but if the thing that's interesting about the session is the confrontation with the serpent king, we can skip right to it with a scene check. The scene check may surface any complications the PCs encountered along the way, while providing them with opportunities to discover raises that may help them in their confrontation with the serpent king.

Hopefully this post has revealed the flexibility of the core mechanic for GMs in OSR+.

It's not rocket science, it's an art!

Now go forth and hit some nails with your new hammers.

Armor

Armor Classes

Classes Conflicts

Conflicts Ethos

Ethos Flaws

Flaws Kits

Kits Maleficence

Maleficence Origins

Origins Shields

Shields Skills

Skills Spells

Spells Stances

Stances Tactics

Tactics Talents

Talents Treasure

Treasure Weapons

Weapons

Hall of Heroes

Hall of Heroes Hall of Legends

Hall of Legends Dungeons & Flagons

Dungeons & Flagons

0 Comments on

Choose Your Check Wisely