Woah, you say incredulously, “My job isn’t to make the game fun? What the heck? What kind of horrible advice is this?” That’s right. Let that sink in for a moment. Your job as GM is not to make the game fun. When you put on your GM hat, you’re not some face-painted juggler looking for laughs or a carnival barker selling a dice game. Fun is a byproduct of what you do as a GM. It is not the goal of playing, it’s an outcome. Fun is what happens when you run the game right.

I bring this up because I see countless posts in RPG design forums (namely on Reddit) where a naïve or otherwise new GM asks if fudging the dice is ever OK, and one of the inevitable (and popular) replies is "Yes it is OK because your job as a GM is to generate fun for the table," or some variation of that. The reasoning goes something like: We are all assembled at the table because we want to have fun, and an RPG is a game, therefore any efforts to maximize fun should be pursued, including the GM lying to the table about how the game operates.

The idea that our primary job as a GM is to make the game fun and that fudging the dice is a way to achieve this is so deeply ingrained that we forget that fudging the dice is cheating. And therein lies a contradiction: how can we be impartial arbiters of the rules if our job involves cheating? It seems to me a hollow victory if the way we make our friends at the table happy is by lying to them.

So let's start by reviewing what actually are the responsibilities of the GM, and then segue into the reasons why we play RPGs at all, before we get to the topic of generating fun.

Sanitation and Sanity

I said above that "fun" should be a byproduct of running the game. It's analogous to how citywide sanitation is a byproduct of the trash man picking up your garbage every week. His job isn't to cater to your standards of cleanliness specifically, his job is to drive a stinky truck around once a week and empty your bins in an orderly fashion. Take a UX designer, as another example. Their job isn't to make humans feel good when they navigate a user interface; their job is to follow design principles so that the user interface is navigable for humans. And this isn't a purely semantic distinction—yes, the trash man cares about sanitation when he does his job, and it's a reason why he wants to do it efficiently, and the UX designer cares about the human experience when she designs the interface, but both of them realize that in order to generate sanitation and sanity, they have to carry out a specific set of tasks that in the aggregate, generate sanitization and sanity.

The GM's actual responsibilities are numerous, and I doubt anyone will ever agree on a perfect list because every RPG is different. But in OSR+, your responsibilities as GM are enumerated as:

- Referee. You adjudicate the rules.

- Director. You manage the spotlight.

- Author. You write an adventure.

- Guide. You mediate the social dynamic of the table.

- Player. You play the game by the rules.

These responsibilities are all about setting up for and running the game; they're not individually about making sure the players are having fun. But let's be clear: they all feed into that fun. Designing an adventure in OSR+ means taking the story hooks your players gave you (which are innately things they are interested in exploring, i.e., things they would have fun doing) and incorporating them into the adventure. When you author the adventure, then, you're implicitly incorporating things into the game that they think will be fun. And when you mediate the social dynamic of the table as its guide, you might make decisions about what sort of game modes to employ during play based on your players' play styles: maybe they're mostly narrativist players who won't appreciate three hours of dungeon crawling and combat, so you plan for lots of downtime and exploration.

The point here is that the doing of these tasks efficiently is a path toward generating a fun experience by default. It's very similar to how we argue that narrative emerges naturally from play when we go through the procedures of the game—we don't come up with narrative first and then retrofit player action to make it happen by negating their choices. When the table isn't having fun, one of the things we can do is reflect on why. And oftentimes it comes down to us not fulfilling one of our responsibilities as a GM, or a player not abiding by the social contract.

All this aside: if your job was primarily to generate fun, how exactly would you go about doing that for the entire table? If Susan likes combat but James prefers giving epic monologues and Mary doesn't care about the mechanics (she just wants to play a bard with a cute familiar), the task "make them all have fun together" becomes impossible to tackle on its own because it's not actionable as a task unto itself.

You end up doing silly things like railroading the adventure and fudging the dice whenever you suspect that Susan or James or Mary won't have fun.

Lying to Your Friends

I could write a whole separate treatise about why fudging the dice is cheating, but I want to focus on why it's not a solution to "making the game fun." When a well-intentioned-but-ignorant GM decides to fudge the dice, he's usually reacting to something that's happened in play he anticipates will make his player unhappy: the NPC Mary's fighting rolled another critical success, and Mary's about to get hammered again. She's been rolling poorly all night and her PC is on its last leg. Or perhaps the party underestimated the bad guys, and as a GM you're facing a TPK (total party kill). So you decide to ever-so-innocently pretend that the roll wasn't a critical success, or you fudge a few rolls on the player side so that their attacks hit, to prevent the TPK from happening.

You're reaching for this (very bad! Bad dog!) tool because you view it as a solution to mitigating what you suspect will be Mary's annoyance with the odds, or the party's disappointment in losing all that time invested in the encounter that results in a TPK. And I understand that empathy you have, trying to protect your players from feeling abused by the capricious nature of the dice (or their own foolish decisions). But you're doing them an even worse disservice by fudging the dice in either of these scenarios, because:

- You're completely abdicating your responsibility as a player in the game. Fudging the dice is ignoring the rules. You're now playing by rules you made up, and the players don't have that luxury in the game. (In other words, you're cheating.)

- You're not letting the players play the game. This is about meaningful choice. If the dice rolls can be subverted by fiat, then they don't represent real choices for the players. You've unwittingly put them on a railroad.

- Most importantly: you're lying to your friends. They believe the dice decide what happens in play for moments like this, but you've decided that the dice only matter if you feel like they do, whenever it suits you, because you think you know better about what your players want out of the game than they do.

Of course, none of this matters if everyone at the table consents to you cheating from time to time. This sort of table would have to be extraordinarily permissive to let you dictate the narrative from the top down, and I'm sure there are tables out there that are OK with this. I personally would have no interest being at such a table, because in my opinion I wouldn't be playing a roleplaying game then—instead, I'd be acting in my GM's stage play or novel, where I get to do things only if it fits into his agenda.

It's consent that makes all the difference. Rulings, for example, are rules you make up on the fly to solve problems. Unlike fudging the dice, rulings work because they are made with the open consent of the table.

How to "Make" Fun

So how do we deal with Mary's disappointment and the time wasted after the TPK?

Stop Looking at Failure as Failure

First of all: we have to stop looking at failure as failure. The dice tell a story as much as the players' choices tell a story. When Mary hits a string of bad rolls, it's an opportunity to embrace the narrative import of her bad luck. Are the circumstances of the encounter dredging up some sort of deep-seated trauma Mary's PC wrestled with in the past, and now she can't get a grip and so she's losing the battle? As a player, you can lean into that, and as a GM, you can frame the seemingly random dice rolls that way. After all, one of your responsibilities as GM is to read the tea leaves and frame the narrative that emerges.

Death Doesn't Have to Mean Death

For the TPK, defeat doesn't have to mean death. Are the PCs captured now? Or if they did die, and the table wants to keep playing with these PCs, is there an adventure to be had in the afterlife? It's OK to pause the game and say, "Okay guys, it looks like this isn't going to end well for you all. Where do we want to take the game next if you're all killed?" These are all possibilities, and I don't know about you, but I'd rather know my options when I'm investing days/months/years in a game as a player than have the GM decide for me because he thinks he knows better.

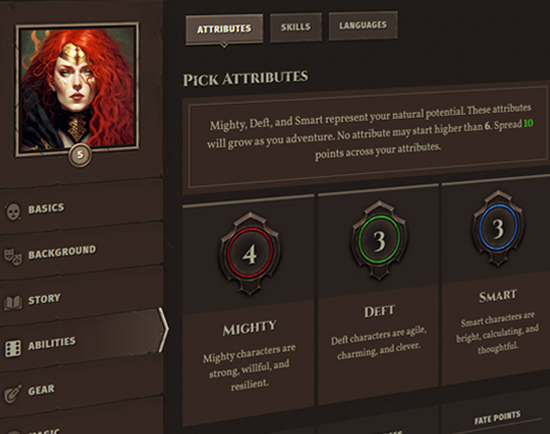

As Always, System Matters

And also, it's worth noting that system matters. If you're playing an RPG with swingy, binary pass-fail rolls (d20 resolution in D&D for example) where there are no non-diegetic mechanics to alter the dice (such as fate points in OSR+), then the system itself is going to frequently yield unpredictable outcomes as a matter of pure math: there's always a 5% chance of rolling a 1. You have to accept as a player or as a GM that that's the sort of play you're going to get out of that kind of system. The solution isn't to cheat or hack the system to make it work the way you want.

Instead, if you want a sort of play that's less swingy and has non-diegetic controls, then you might consider a system from the PbtA tradition (2d6, which generates a bell curve), where every roll amounts to a success check. Players are more likely in such systems to roll success-at-a-cost, where there's a gray area for negotiation as to what happens between player and GM.

Or maybe you can just try OSR+, and get the best of both worlds 😊.

P.S. Please don't lie to your friends. It's not nice.

Archetypes

Archetypes Armor

Armor Classes

Classes Conflicts

Conflicts Cultures

Cultures Ethos

Ethos Flaws

Flaws Glossary

Glossary Kits

Kits Maleficence

Maleficence Origins

Origins Shields

Shields Skills

Skills Spells

Spells Stances

Stances Status Effects

Status Effects Tactics

Tactics Talents

Talents Techniques

Techniques Treasure

Treasure Weapons

Weapons

Hall of Heroes

Hall of Heroes Hall of Legends

Hall of Legends

Dungeons & Flagons

Dungeons & Flagons

james

Books and the rules in the of the game are guidelines that in place to fall back on, not dictate the game. The TRUE spirit of the OSR is story trumps rules, and DM/GM makes adjudications to keep the fun moving. The DM/GM is no clown looking for laughs, but he should provide an experience for players in his world.